In The Great Divorce, C.S. Lewis spins a story of hell as a place that souls inhabit by choice. One of the common motivations for remaining in hell is for the nursing of grievances. The same principle is made explicit in his preface to The Screwtape Letters:

We must picture hell as a state where everyone is perpetually concerned about his own dignity and advancement, where everyone has a grievance, and where everyone lives with the deadly serious passions of envy, self-importance, and resentment

C.S. Lewis, The Screwtape Letters, (1961 Preface p. IX)

In a previous post I reflected on Galen Guengerich’s new book on gratitude as a spiritual practice. Grievance is the opposite of gratitude, and, alas, can also take on the character of a spiritual practice. That is, it becomes a motivating value on which our minds fixate.

James Kimmel, Jr, the director of Yale Medical School’s Collaborative for Motive Control Studies, argues that grievances fire up the brain in a way that is very similar to addictive drugs. Dwelling on a grievance activates the same neural reward circuits as narcotics.

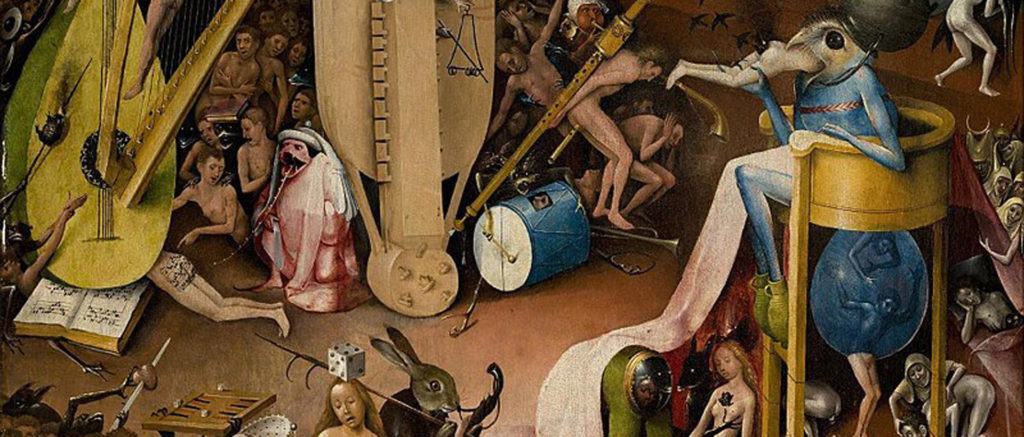

(cc Wikimedia)

There is also a social element to grievance. Grievances help bind communities together. They can spread from one person to another. The desire to share grievances can lead to a kind of grievance evangelism. Groups with a shared sense of grievance can become an echo chamber that amplifies a grievance fixation.

There has been much speculation on the spiritual commitments of Donald Trump. He does come across as the poster child for the grievance-centered life. The Washington Post reports today that “In a cascade of tweets sent after midnight, [President Trump] shared more dubious claims of electoral fraud and falsely insisted, yet again, that he was the true victor.” This leads the mind rather quickly to C. S. Lewis’s description of the “ruthless, sleepless, unsmiling concentration upon self which is the mark of Hell.”

Following this line, Kimmel puts grievance at the core of Trumpism. Trump built his movement around a populist resentment of “liberal elites.” Now, the myth of a stolen election is becoming a binding belief for the true faithful (and a creedal test for cowed Republican officials).

We shouldn’t pretend that grievance doesn’t help bind Democratic partisans as well. Anti-Trumpism is clearly the glue for the diverse views that gathered in the big tent of the Democratic Party of 2020.

Kimmel argues that grievance as a motive force can be highly destructive. This is certainly true, but it’s also essential to recognize that grievances can be about real injustices. The civil rights movement of the 1960s and the Black Lives Matter movement today could certainly be characterized as organized around grievances. So too, the centerpiece of the American Declaration of Independence was a list of grievances.

There are, then, two key questions to confront. The first is: how do we identify legitimate, and even urgent grievances? The second is how do we manage the pathologies of grievance both on an individual and collective level?

Part of the answer to both of these questions on a social level is that this is precisely what our political and legal institutions are for. That they aren’t always that good at it is a reflection of their inevitable imperfections, and of the enduring difficulties of solving these core human problems.

At the individual level, introspection and self-care are essential. But, let’s also return to gratitude. More important than its place as the conceptual opposite of grievance, a focus on gratitude can serve as an antidote to a grievance-fixation.

And, going back to C. S. Lewis’s description of hell as a place of interminable self-centeredness, work to address the legitimate grievances of others may be a healthy road map for a life of purpose.

Meanwhile, this ties to a central point in my new book manuscript: that the purpose of life is to love and be loved, and that an essential characteristic of love is taking the interests–and thus the grievances–of others as seriously as your own.

The bottom line, still, is the need for an appropriate balance between attention on the important work of addressing legitimate grievances and on a life perspective of gratitude.