[By Sludge G-CC BY-SA 2.0]

Women’s equality is clearly one of the most important social justice ideas of the modern era. It is a curious thing, then, that so many men who have led our thinking about ethics and social justice failed to appreciate this elemental fact. These same men had groundbreaking insights in other areas and ongoing interactions with exceptional women that should have opened their eyes to the underlying truth of women’s equality. This is a phenomenon I call male pattern blindness.

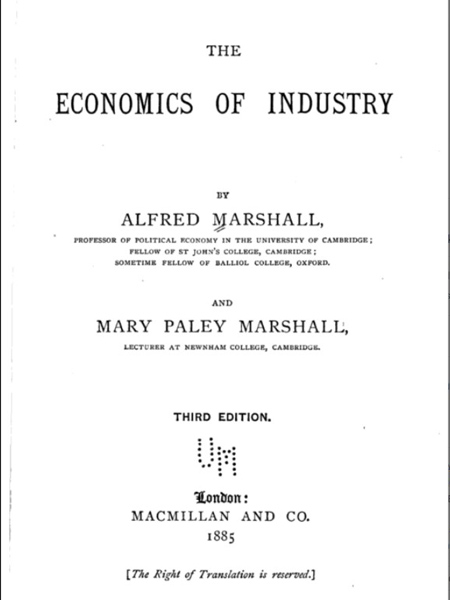

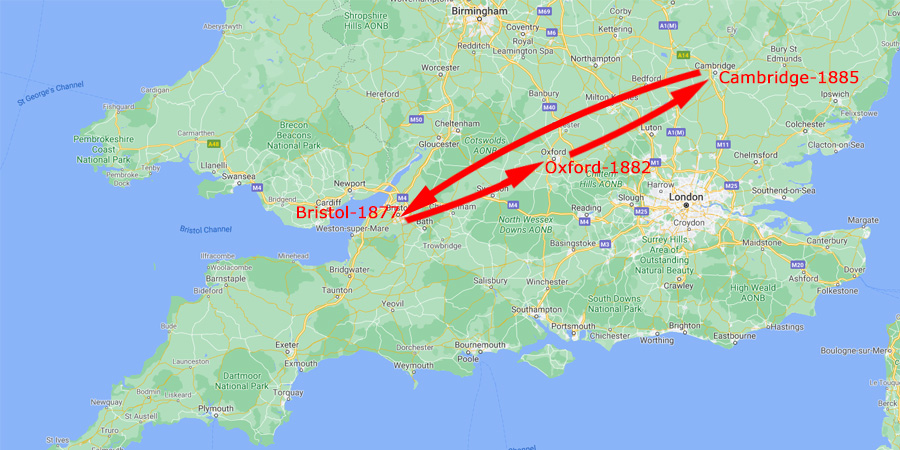

My current project on the idea of women’s equality includes discussion of some of the stupid-brilliant men who suffered from male pattern blindness and slowed the movement away from patriarchy. I am highlighting four of them in this blog. I have previously profiled the moral philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, the women’s physician Charles Meigs, and the economist Alfred Marshall. This week, the spotlight turns to my final example, the theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer (1906-1945).

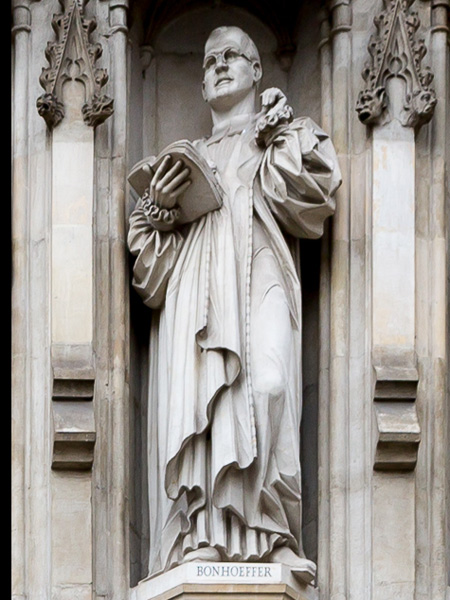

Westminster Abbey

[Photo by CEphoto, Uwe Aranas

CC BY-SA 3.0]

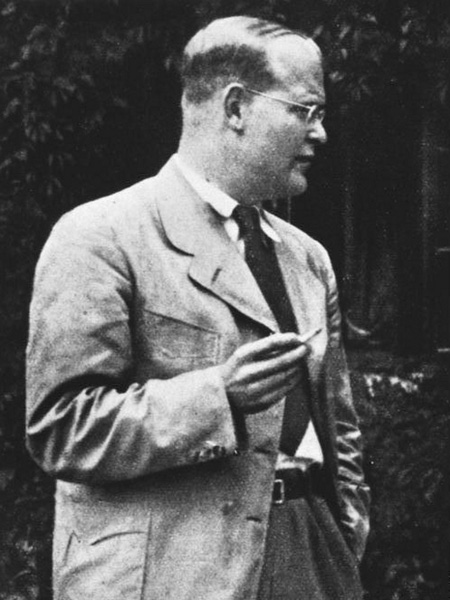

Dietrich Bonhoeffer is broadly and appropriately revered. He is about as close as contemporary Protestants get to having a saint. He took a courageous stand against the Nazi subordination of religion in Germany as one of the founders of the Confessing Church and the leader of their underground seminary at Finkenwalde.

In 1939, with the world on the brink of war and the Nazis arresting and persecuting the leaders of independent churches, Bonhoeffer was able to leave Germany. Yet he returned, believing that he needed to be in Germany to help rebuild the church once Nazism was defeated.

Family connections got Bonhoeffer a spot in a special unit of German military intelligence (the Abwehr). This posting allowed him to remain in touch with the global ecumenical movement and protected him from regular military service. It also connected him to the highest levels of the anti-Nazi resistance.

Bonhoeffer’s participation in the resistance led to his arrest in April 1943 for helping Jewish refugees escape to Switzerland. Later, he was tied to the failed July 20, 1944 attempt to assassinate Hitler. He was executed at the Flossenbürg concentration camp in April 1945, just two weeks before its liberation and one month before Germany’s unconditional surrender.

[US Army Photo]

There were several important women in Bonhoeffer’s life who should have helped him see the equality of women. Most important, surely, was his twin sister, Sabine, with whom he remained very close throughout his life.

Bonhoeffer also worked closely with two women—Elizabeth Zinn and Bertha Schulze—who had doctorates in theology and played a strong role in his intellectual development. Another close friend and confidante was Ruth von Kleist-Retzow, an outspoken and active anti-Nazi and a major sponsor of the Finkenwalde seminary.

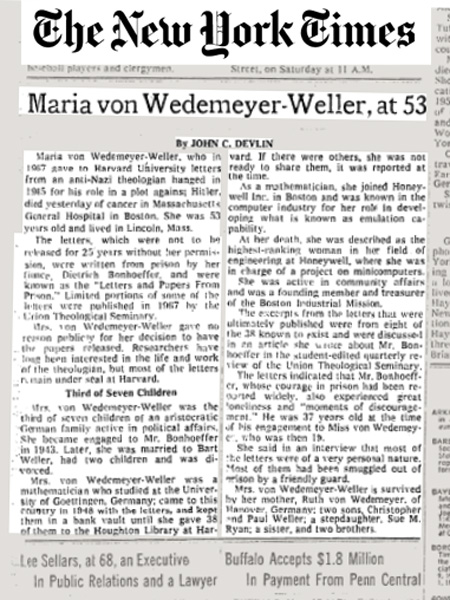

[NY Times 11/17/1977]

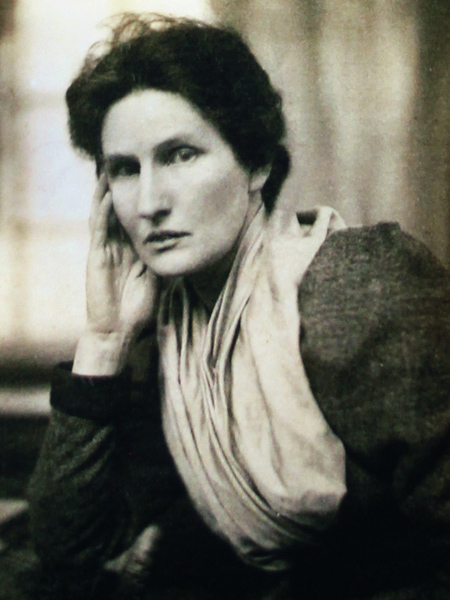

Bonhoeffer never married, although he became engaged to Kleist-Retzow’s granddaughter Maria von Wedemeyer in January of 1943. Wedemeyer was just 19 years old (to Bonhoeffer’s 37) and the engagement came only three months before his arrest. This makes it difficult to assess how their relationship might have contributed to an appreciation of women’s equality. After the war, Wedemeyer did go on to an impressive career as a mathematician, computer programmer, and business executive.

In addition to this personal context, Bonhoeffer’s theological ethics—like Schopenhauer’s moral philosophy, Meigs’s medical work, and Marshall’s social-welfare economics—should have made him highly receptive to the idea of women’s equality.

Through all the trauma of his war experience, Bonhoeffer continued to develop an important and influential body of theological work. A central element in his ethics was the idea of “being there for others.” He argued for learning to see “the view from below.” This was a call for understanding the way privilege and power distort one’s sense of what it means to care for others. Because of this perspective, Bonhoeffer has often been used to advance theological conceptions of social justice, including feminist theology.

This is a reasonable appropriation, but Bonhoeffer himself was not open to the core principles of feminism. In fact, he identified the subjection of women as a mandate directly from God:

[T]his rule of life is so important that God establishes it himself, because without it everything would get out of joint. You may order your home as you like, except in one thing: the wife is to be subject to her husband, and the husband is to love his wife.

Bonhoeffer emphasized that “the equality of husband and wife … is modern and unbiblical.” Almost 100 years after the Declaration of Seneca Falls, one of the most innovative and important thinkers in the Protestant world—a man who argued for seeing the world from the perspective of those with less privilege and power—still thought it “an unhealthy state of affairs when the wife’s ambition is to be like the husband.”

Bonhoeffer had the theological tools to see the importance of women’s equality. He was prepared to apply these tools to advocate for the importance and dignity of many oppressed groups. He failed, however, to see the limitations placed on women. And he did so despite personally knowing women of exceptional abilities and aspirations. Dietrich Bonhoeffer was a man who should have known better, but didn’t.

Moral: Adopting a “view from below” doesn’t help if the women around you are invisible.

Next up: Some concluding thoughts on what it all means.

Previous Profiles:

- Arthur Schopenhauer, a giant of moral philosophy and misogynist prejudice

- Charles Meigs, a prominent physician and a pillar of patriarchy

- Alfred Marshall, an economist’s economist and chauvinist’s chauvinist

The Overview: Male Pattern Blindness

Four Men Who Should Have Known Better:

Four Men Who Should Have Known Better: Four Men Who Should Have Known Better:

Four Men Who Should Have Known Better: